Hi there!

It is summer, and I have a number of upgrades in mind for my outdoor living areas: some involving electric upgrades, some involving gardening, some involving landscaping.

One thing I have in mind involves the night illumination of the gazebo and its surroundings. The current illumination is based on low power LED strings, powered by batteries recharged during the day by small solar panels.

However, I found that this kind of illumination has a lot of drawbacks. First of all, the lights are very dim. They are just fine when entertaining guests having conversations while enjoining the freshness of the evening air. But when it comes the time to do some table game that requires being able to look at pictures or reading stuff, often we end up going inside where we can have more light.

In addition, I need to turn on and off the lights manually, whenever I need them. If I leave them always on and let their sensors take care of the switching, they end up using the whole battery by the middle of the night and, sometimes, they take so long to recharge that by the time it is evening they don’t last that much anymore.

The solution would be to use bigger solar panes, but the batteries are still small and they also need their time to recharge. If I let them recharge too fast, they will start loosing their capability of retaining the charge too soon, and I would have to replace them relatively often. So I would trade off the usage of solar panels with more waste in exhausted batteries.

The right thigh to do, in my view, is therefore to use regular 120V lamps, obviously low power LED, but brighter than the ones I currently have. The thing is that I do like the automatism of having them turn on and off automatically from dusk to dawn. So, I thought I could design and build my own dusk to down automatic switch, which actually require just very few component and it is very cheap to make.

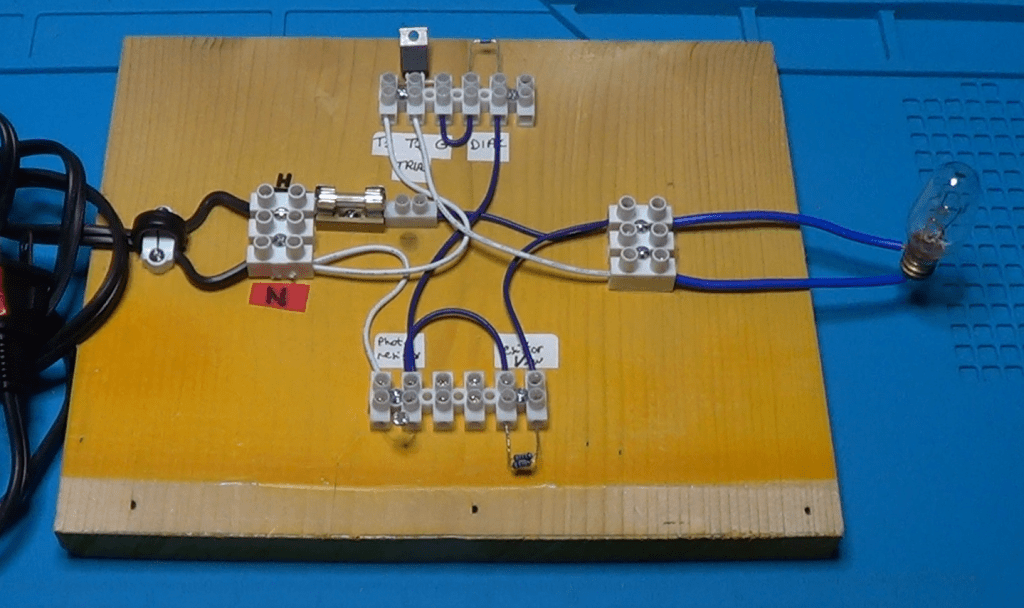

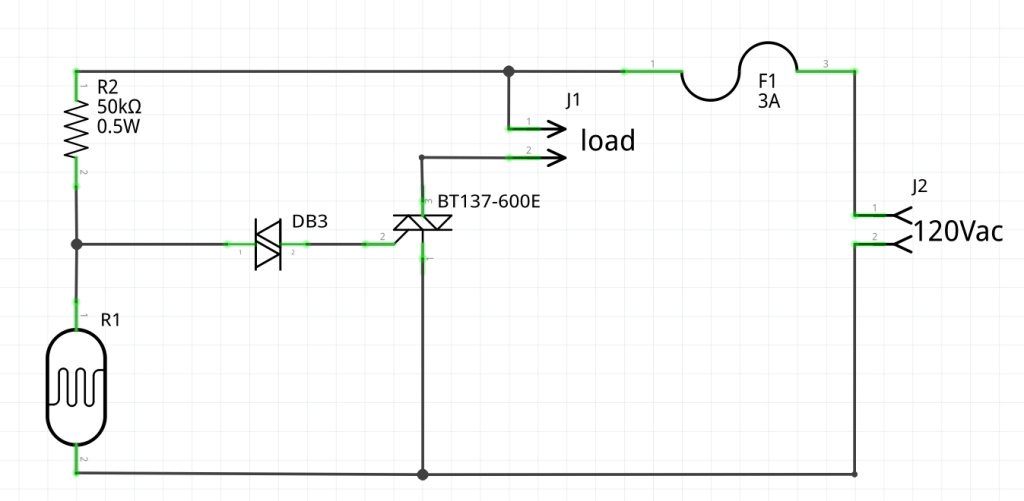

Above is the schematic of my dusk-dawn automatic switch. It is a very standard design, and it requires just a few components.

The load is basically made of the LED lamps we want to control.

The 120Vac input goes directly through a protection fuse and to the series of a 50K resistor and a photo-resistor which is the sensor that will detect the daylight condition to turn the light bulbs on and off.

When there is enough daylight, the resistance of the photo-resistor is very low, in the range between 1K and 4K. When we are getting closer to dusk, the daylight starts dimming and the resistance instead increases. Once the resistance hits the 16K threshold, the voltage at its leads goes above 30Vac.

It is at this point that the DIAC starts conducting and it triggers the TRIAC. The TRIAC, in turn, will let the current flow through the load, thus turning on the lights.

Very simple right?