In the last episode, we talked about the capacitor—the component that stores energy in an electric field and hates it when voltage changes. Today, we meet its magnetic twin.

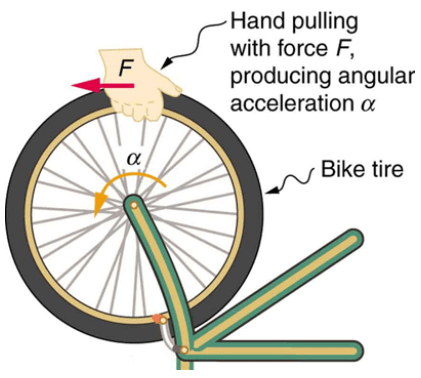

If I try to spin a wheel instantly, I cannot do it. Since the wheel has a mass, it has inertia and so it resists being moved. However, once it is finally spinning, if I try to stop it suddenly…. again, it fights me and prevents me from doing it.

In the world of electronics, we have a component that does exactly the same thing, but with the current. Like the capacitor tries to keep a constant voltage at its leads, the inductor tries to keep constant the current that flows through it with the help of a magnetic field.

It is the most stubborn component in a circuit. It is basically the mass of a circuit. If current is not moving through the wire, it doesn’t want it to start. If current is already moving through the wire, it doesn’t want it to change, or even stop.

Today, we are going to look at the physics of the inductors, why they can be dangerous, and how they are used in real world applications.

Anatomy of an inductor

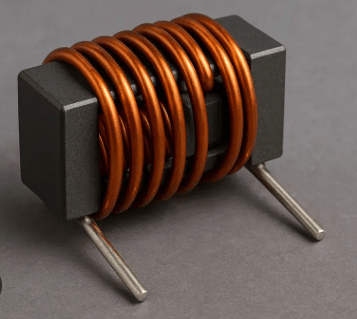

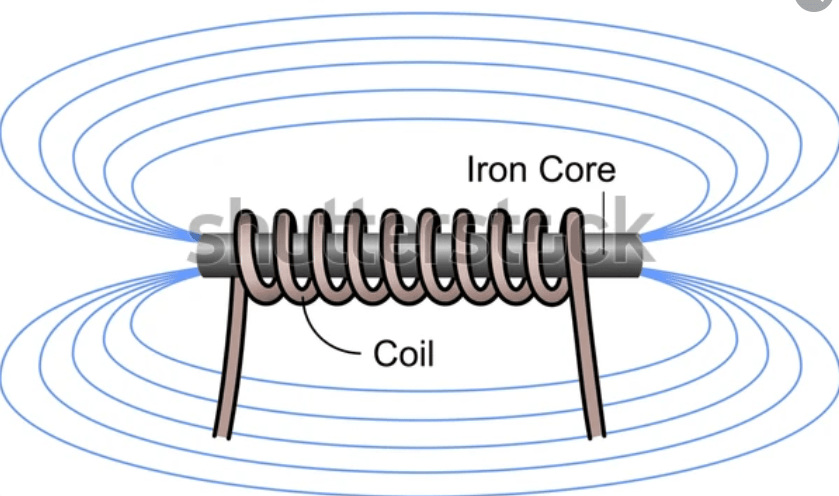

Physically, an inductor is the simplest component you’ll ever see. It is usually just a coil of wire. But don’t let the simplicity fool you.

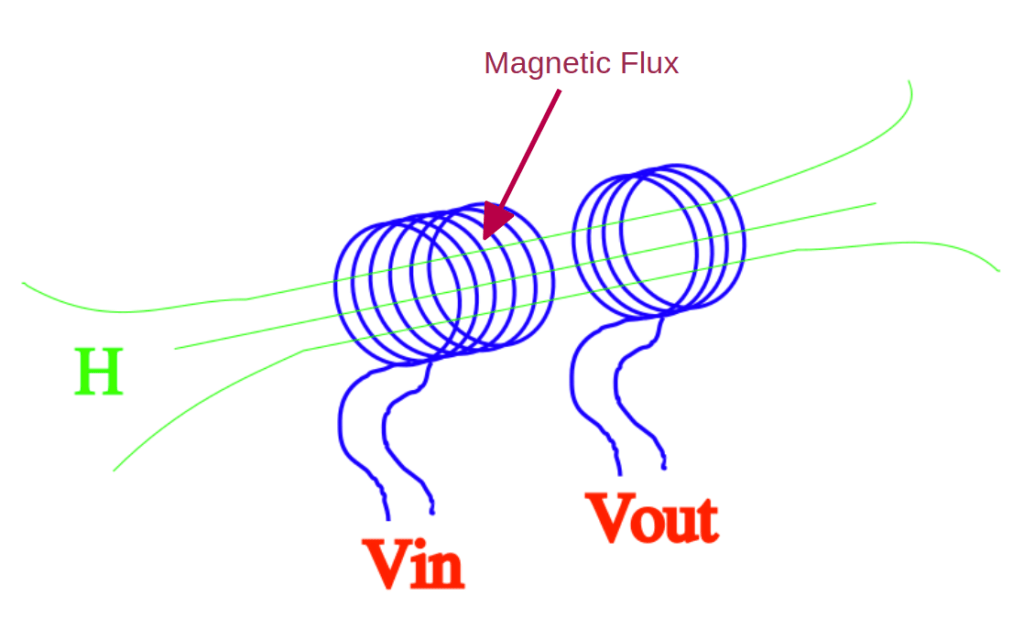

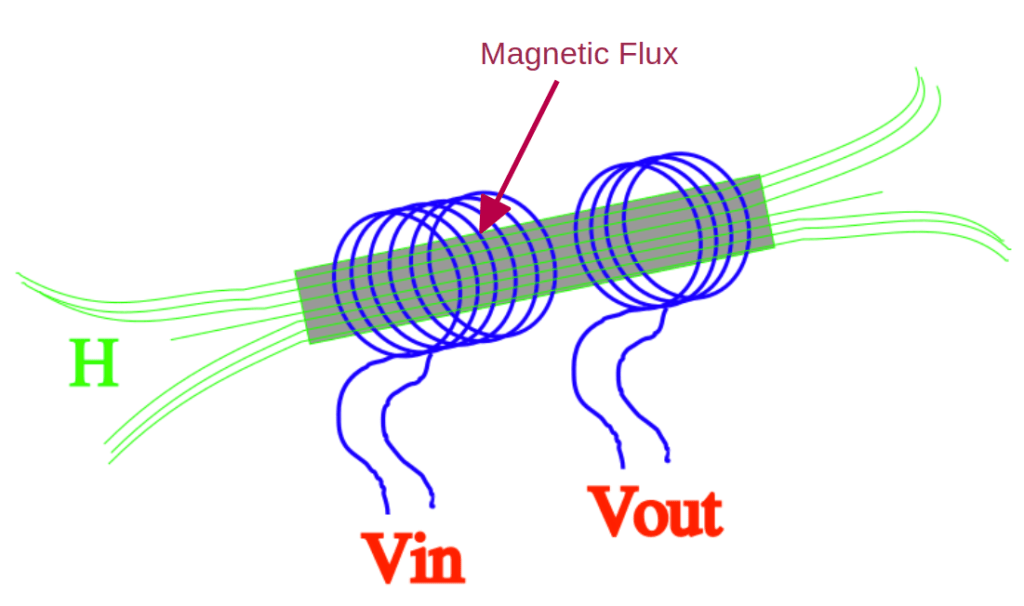

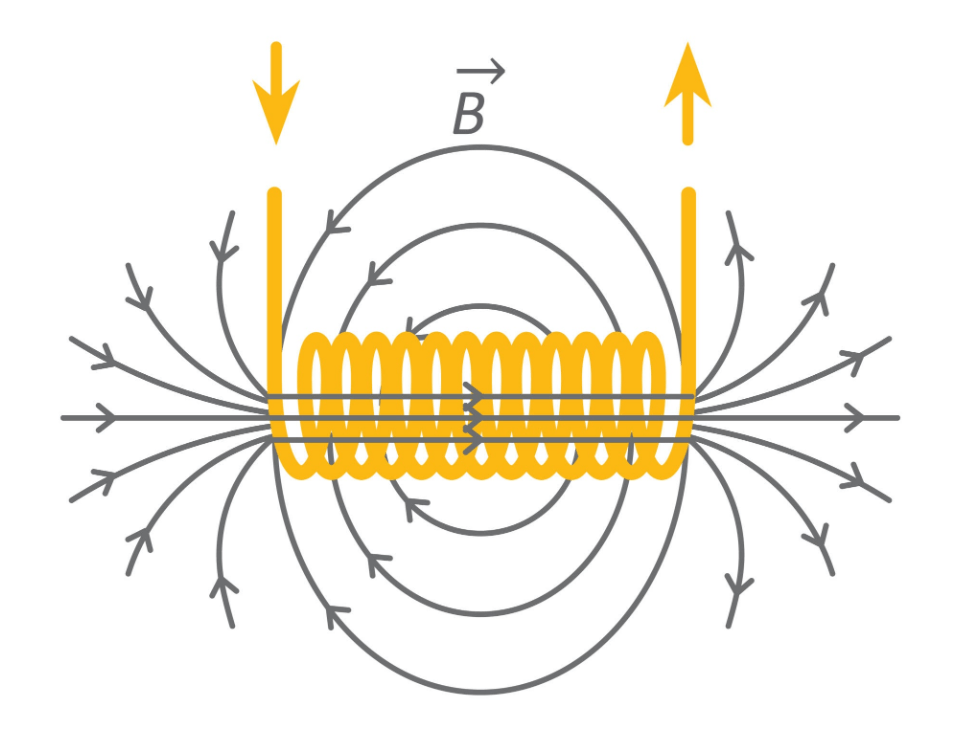

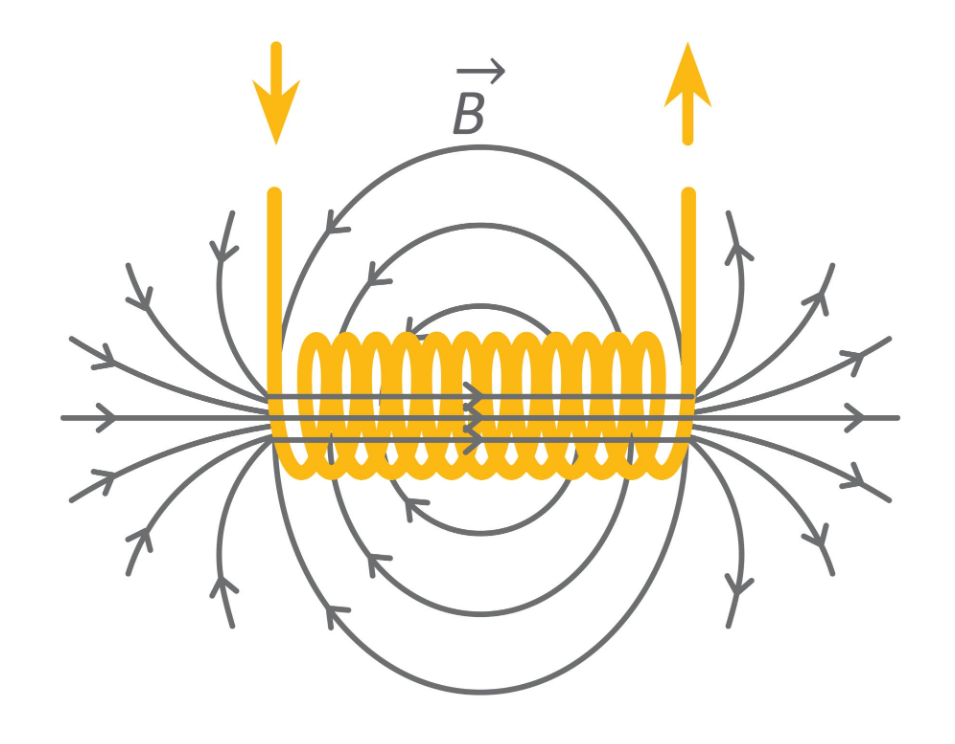

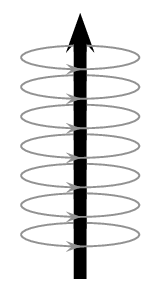

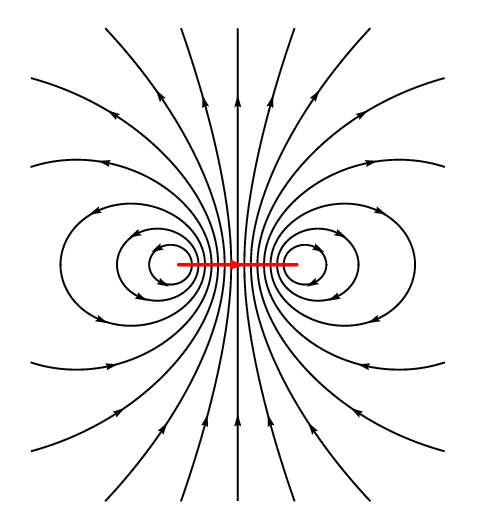

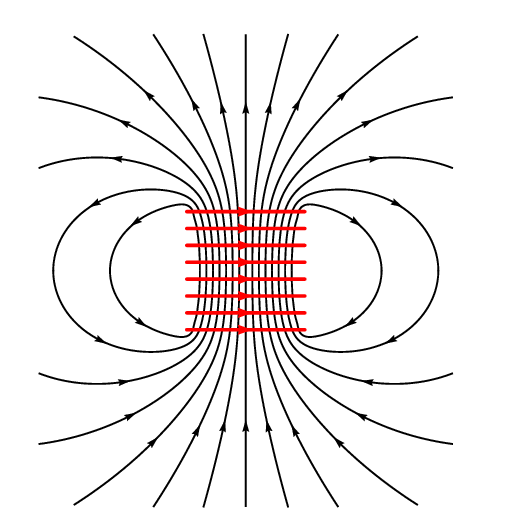

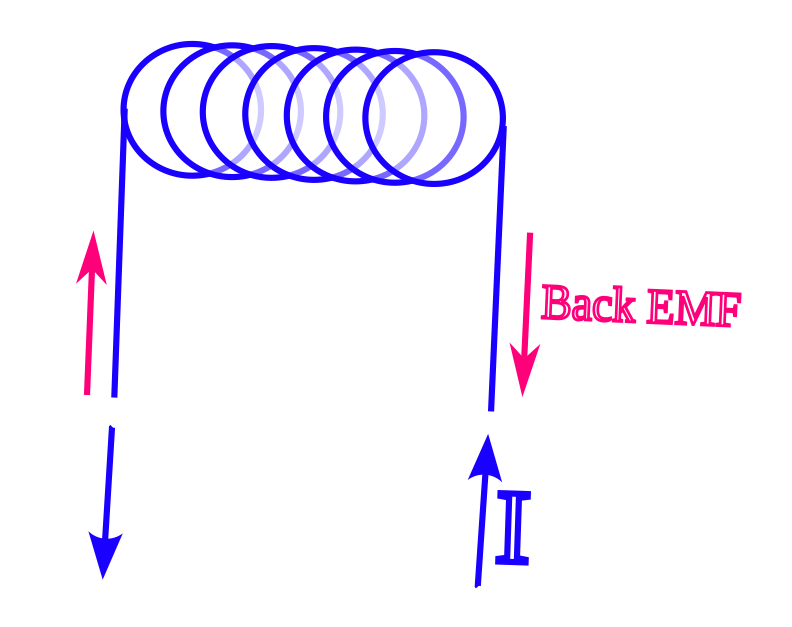

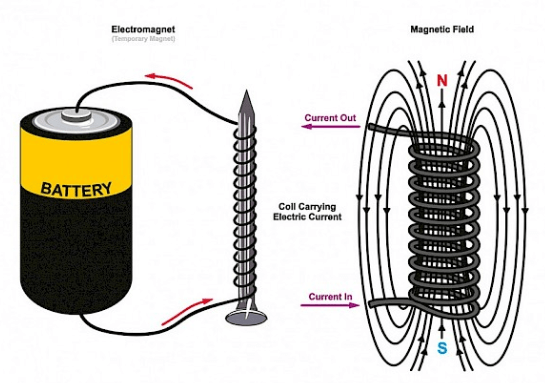

When current flows through a straight wire, it creates a small magnetic field around it. But when we wind that wire into a coil, a shape that we call solenoid, those individual fields stack up and reinforce each other.

This creates a concentrated magnetic field through the center of the coil. And this is where the energy lives. While capacitors store energy in an electric field between plates, inductors store it in a magnetic field within the coil.

Additionally, what’s inside the coil matters just as much as the wire itself. We call the inside of the coil “core”.

If the core is made out of air, the strength of the field is low, and such inductors are normally used for high frequency circuits.

If the core is made of iron or similar ferromagnetic material, it will channel the magnetic flux and will intensify it, making the inductor capable of storing a much greater amount of energy.

If the core is made of ferrite, which is a ceramic like material containing usually silicon and iron, then the inductor acquires a much faster capability of switching from on to off and viceversa without the energy loss that we would get with solid iron.

The ability of the coil to store energy in a magnetic field is called inductance, and it is measured in Henry, named after Joseph Henry, who discovered this property around the same time as Michael Faraday. The measure Henry is indicated with the capitol letter H.

How the inductor works

So, why the inductor resists to current changes? It comes down to a fundamental rule of physics called Lenz’s law.

When we try to increase the current through an inductor, the magnetic field has to expand. But the expansion actually pushes back against the incoming current. We call this Back EMF, or Back Electromotive force. It’s basically like trying to push a heavy car: it takes a lot of effort just to get it rolling.

Let’s look at the math, but don’t let that scare you. It is just a way to describe the stubbornness of the inductor.

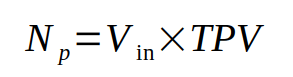

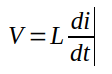

The voltage V across an inductor is defined by

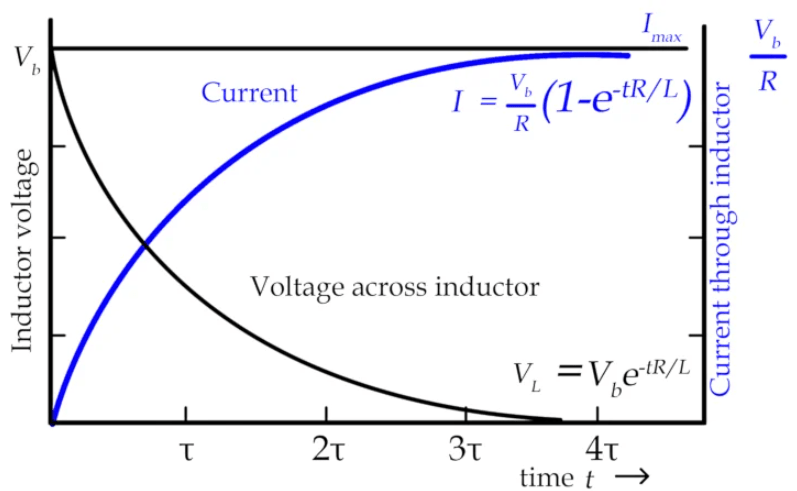

where L is the inductance and di/dt is simply the speed at which the current is changing.

Here is the magic: when we try to push current through, the magnetic field expands. According to Lenz’s law nature hates a change in magnetic flux. And so, the expanding field creates its own internal voltage, the back emf, that pushes back against the battery. It is literally an internal “ghost battery” fighting the actual battery.

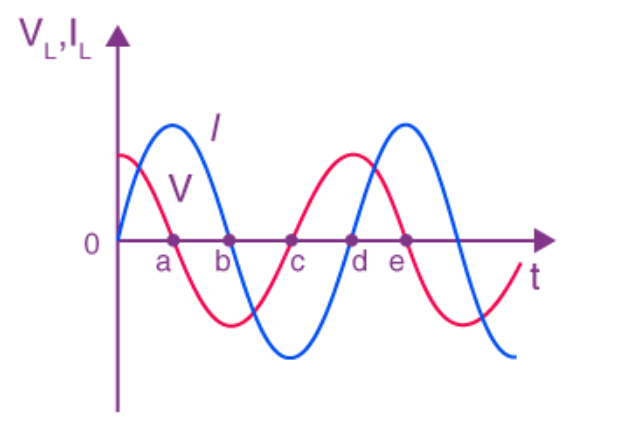

Inductor behavior in DC vs. AC

Now, because inductors react to change, they behave totally differently depending on the type of electricity we feed them.

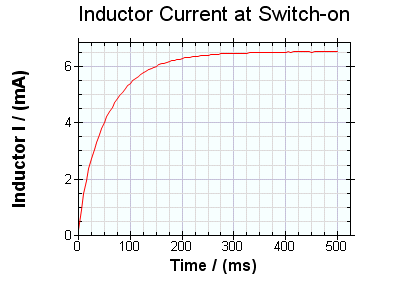

In a DC circuit, when we first flip the switch, the inductor fights the current. It acts like a wall, an open circuit. But, once the current is flowing steadily, the inductor gives up, it becomes just a regular piece of wire.

In an AC circuit, the current constantly changes direction. This means that the inductor is constantly fighting. We call this “fighting” Inductive Reactance. The higher the frequency of the AC, the harder the inductor fights it.

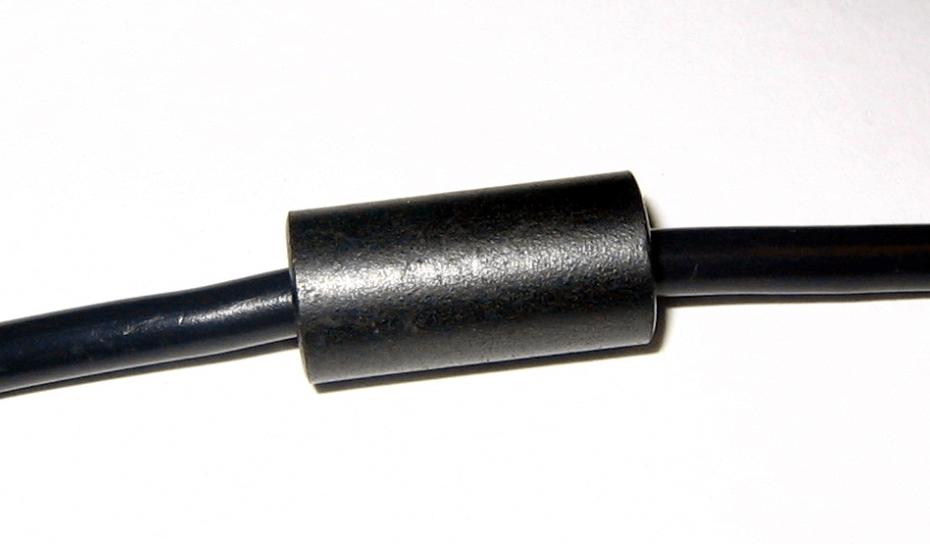

This makes them perfect for filtering out high frequency noise. They let the slow, steady power through, but block the high frequency noise. This is why you see those lumps on the laptop charging cables. They are actually inductors blocking the high frequency interference.

Real world applications

So, where do we actually use these things? Here are a few examples.

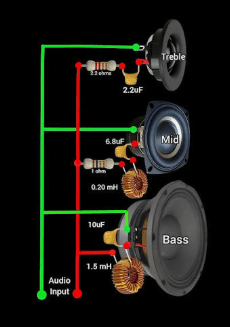

Filters: in the audio speakers inductors are used in crossovers to block high frequency sounds from reaching the woofer, ensuring it emits only those deep, clean, bass notes.

Chokes: used in power supplies to smooth out ripples in the current.

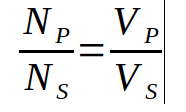

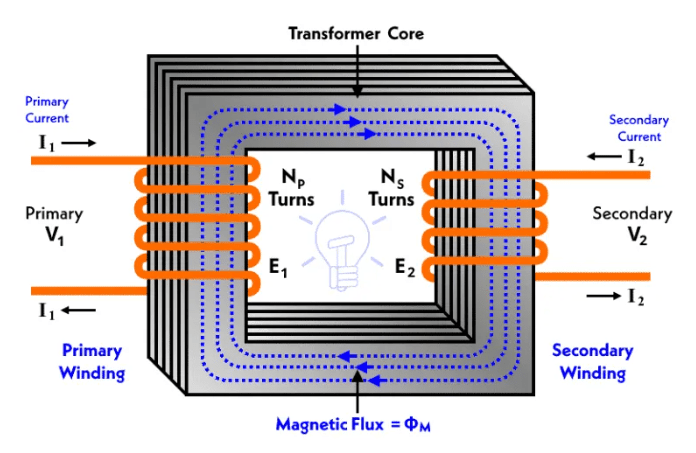

Transformers: if we put two inductors next to each other, the magnetic field of one can induce an EMF in the other. And that’s how they step power up or down for the electric distribution grid.

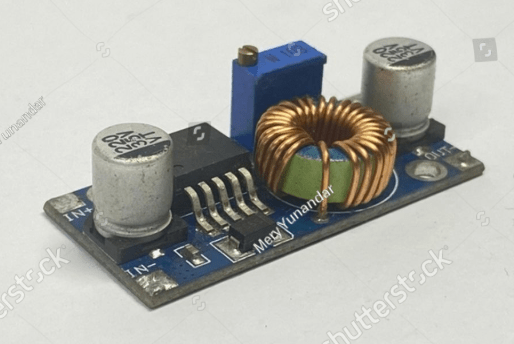

Buck converters: they are made with small transformers working at high frequencies.

Electromagnets: simple coils, usually winded around a ferromagnetic core, that becomes real strong magnets when we make a current flow through their wires. They are used all over the places. And they are especially common inside electric motors, like the ones that power many kitchen appliances.

Sensors: have you ever seen those loop of wires buried under the asphalt at traffic lights? Those are inductors. When a car sits over them, it changes the inductance, telling the traffic lights circuitry that a car is there waiting for its turn to pass.

The inductive kickback

A word of warning now. Because an inductor wants to keep a constant amount of current, it can be dangerous at times.

If you have current flowing through a coil and you suddenly pull the plug, the magnetic field inside the coil collapses. But the energy in that magnetic field needs to go somewhere. What happens is that the inductor will convert that energy in a voltage spike with the polarity oriented in such a way that it will try to keep the current flow without a change.

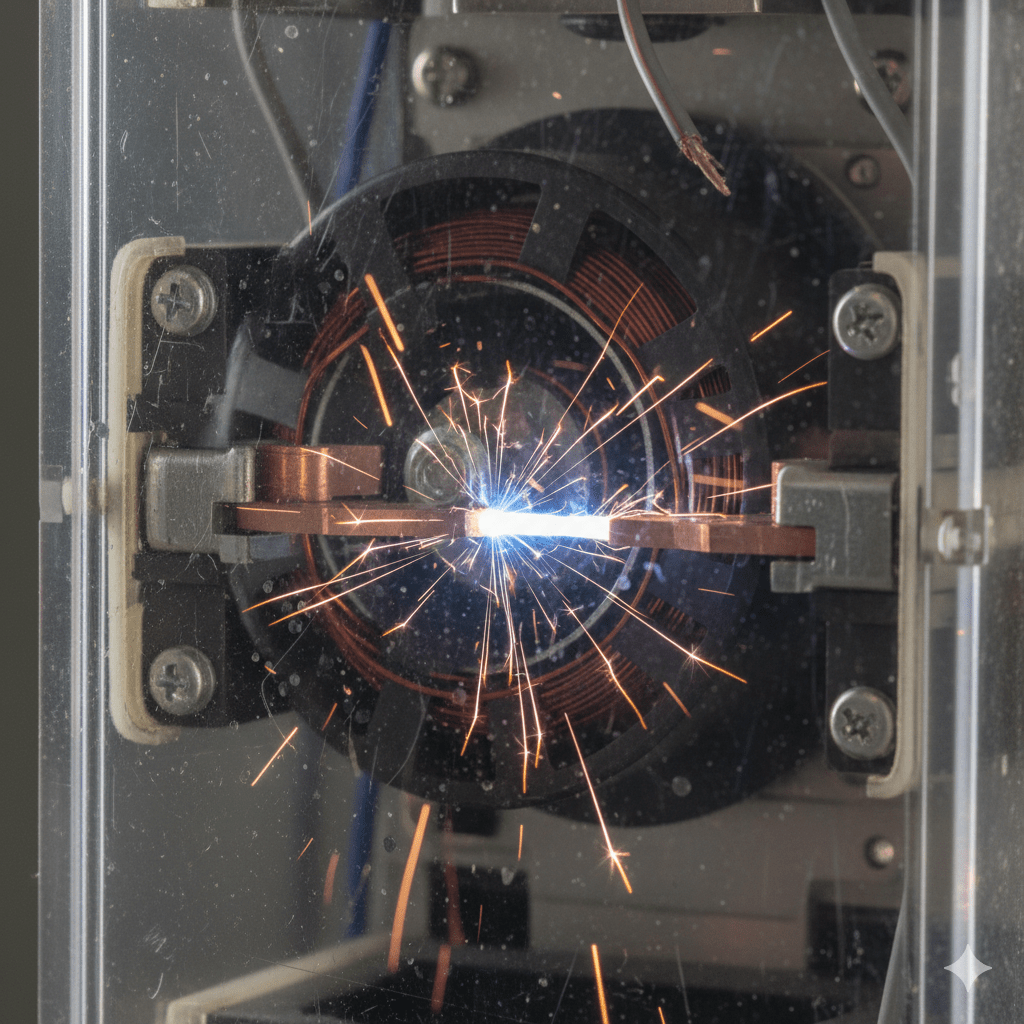

Have you ever seen a spark when you suddenly disconnect a wire from a circuit where current was flowing through it? That spark is caused by this inductive kickback produced by the inductance in the circuit. When you open the circuit, the inductor will generate a voltage high enough to make the current go through the air around the disconnected wires, thus the spark.

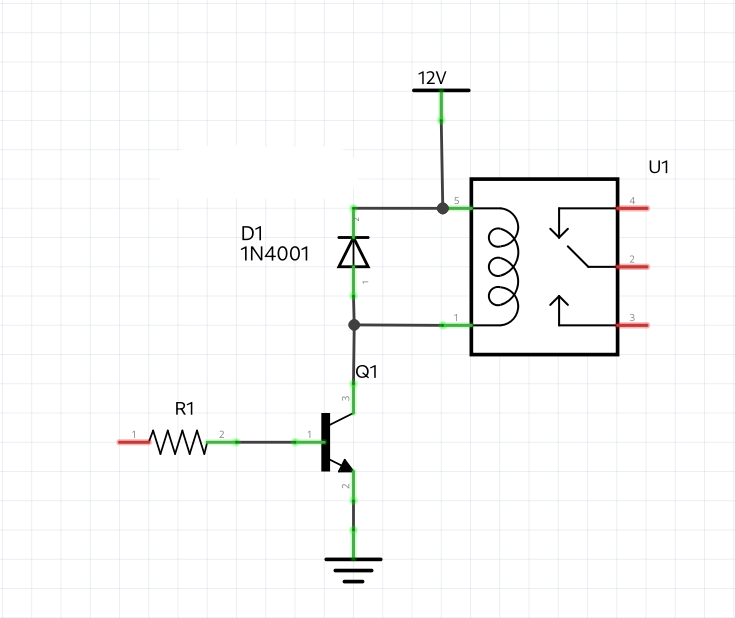

In electronic circuits, the inductive kickback may damage the semiconductors in the circuit. In such a case, we use a diode, in parallel with the inductor, oriented in such a way that it will behave like a short circuit toward the back EMF of the kickback, and it will behave like an open circuit during normal operations.

Here is an example: a transistor controlling the coil of a relay. The diode in parallel to the coil will short the kickback which, otherwise, would destroy the transistor.

A diode connected like that is called flyback diode, because it will make the kickback fly away.

Inductor identification

Now that we know how inductors work, we need to know how to identify them on a circuit board. Unfortunately, this is trickier than it sounds, because inductors are masters of disguise.

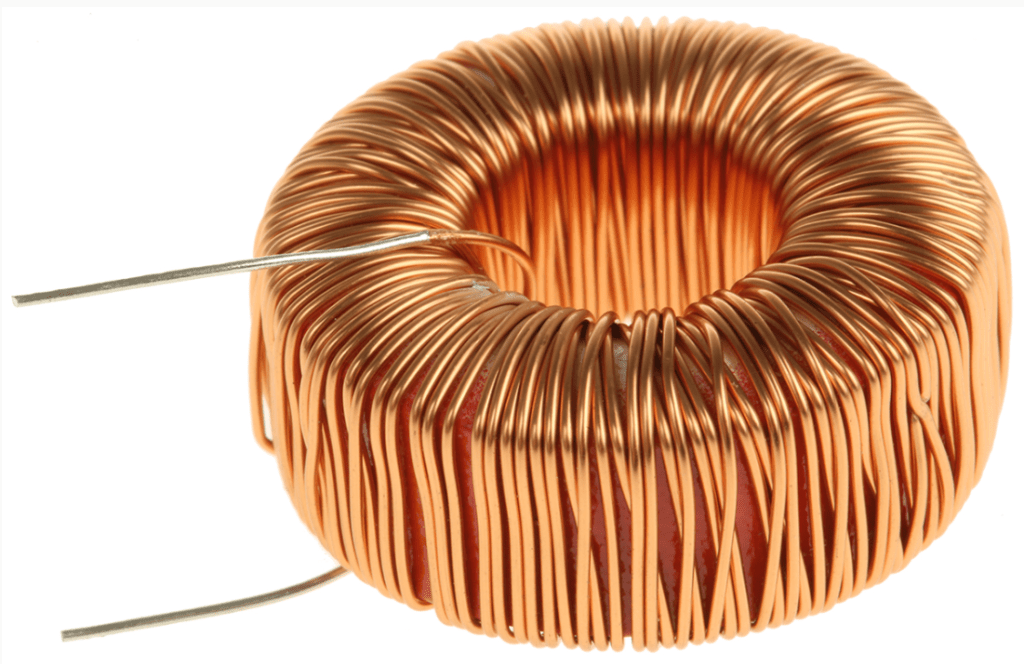

Let’s start with the physical shape, and there are several of them.

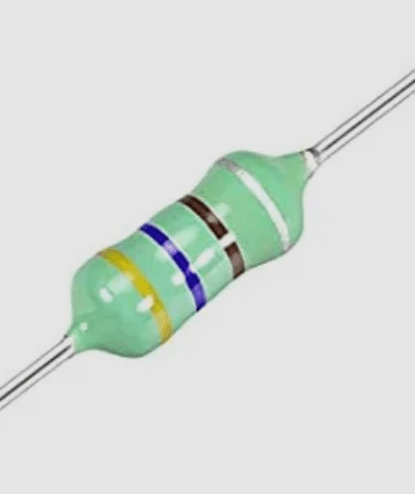

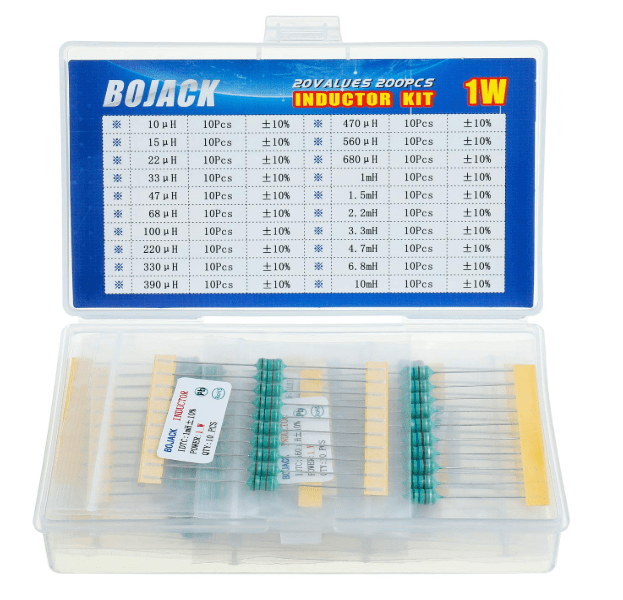

The first kind of shape is the axial inductor: these look exactly like resistors. They are small, usually green of cyan, and have color bands.

A pro-tip for you. If the body looks like a sea-foam green, then it is most always an inductor. If it is tan or blue, it is likely a resistor.

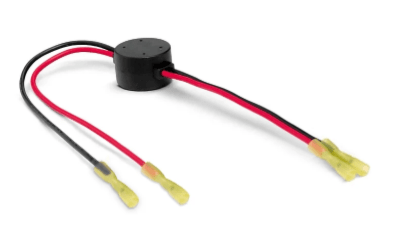

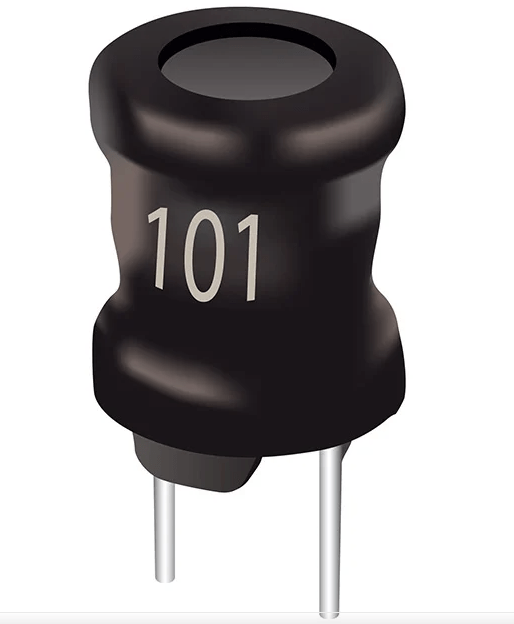

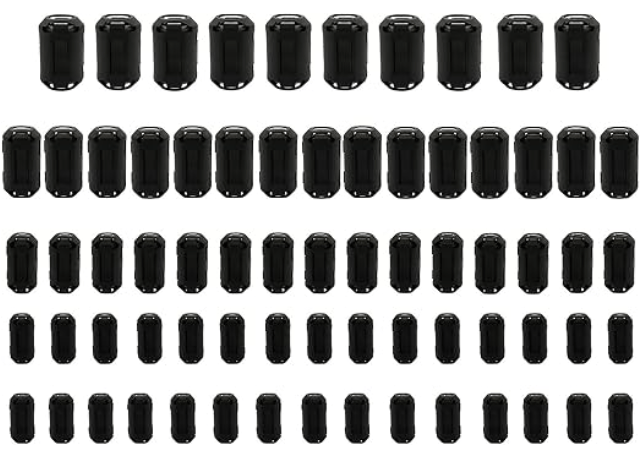

The second inductor shape is the drum or radial inductor. These look like little black mushrooms or weights. You’ll see the copper wire wrapped around a ferrite core, often covered in clear or black shrink wrap.

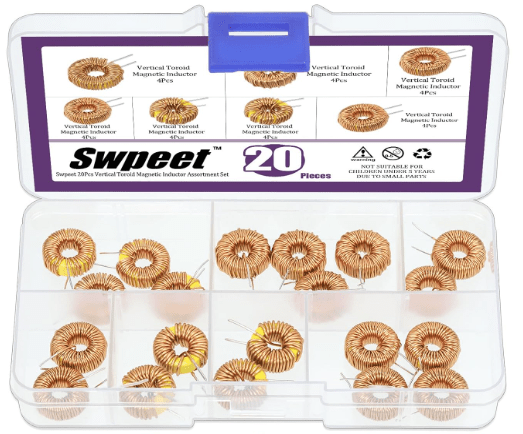

The next shape is the toroid. These are like small donuts. They look like a ring wrapped with wire. In this category we find usually high performance inductors used in power supplies.

Last category I would like to talk about is the one of the SMD inductors. On modern boards, these look like tiny gray or black ceramic rectangles. Unlike resistors, they are usually taller, since they need space for winding the coil.

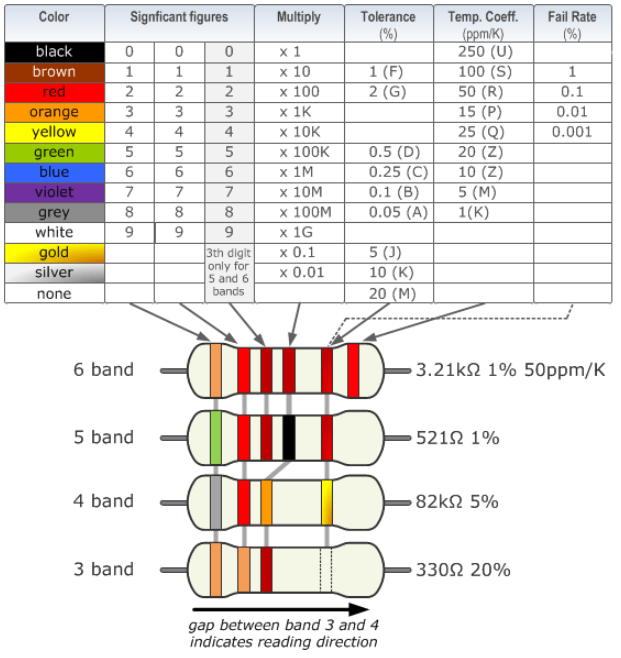

Now, how do we figure out their inductance value? Well, just like resistors, inductors use a code system. Their base unit for these codes is almost always the microhenry.

Let’s start with the color code, used for axial inductors. It’s the same colors used for resistors: black for 0, brown for 1, red for 2, and so forth.

Inductors can have 3, 4, or 5 bands, like resistors, and they are read exactly the same way as the resistors.

For example, the axial inductor from above has yellow, blue, black, and silver, which means 46 microhenry, and a tolerance of 10%.

Let’s now talk about the numerical code, present on the SMD and drum inductors. You might see a 3 digit number, like in the above drum indicor which shows on its case 101. The first two digits are the value, the third is the number of zeros after the first two digits.

This means that 101 translates to 10 + one zero, which means 100 microhenry.

Like with resistors and capacitors, if in doubt, don’t guess, measure the value. The problem is that multimeters usually do not have a mean to measure inductors. You can still test the resistance which, for good inductors, should be almost zero, since it is just a coil of wire.

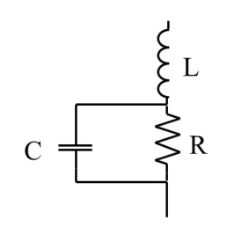

If you want to really measure the value, you’ll have to acquire an instrument called LCR meter, which is a high specialized instrument that take only measurements of inductors, the letter L, capacitors, the letter C, and resistors, the letter R.

The essential starter kit

Now, if you want to start using inductors in your experiments, you don’t need to buy every inductor on the market. Inductors are expensive and bulky compared to resistors, so you want to be strategic. Here is my “starter kit” recommendation for any hobbyist lab.

Begin with a must-have assortment. Don’t start buying individual values. Go to Amazon or eBay and look for an Axial Inductor Assortment Kit.

You’ll get usually 200 or 300 pieces in a small plastic box, with a bunch of different values.

They look like resistors, and fit perfectly into breadboards. The values usually range from 1 micro henry to 10 milli henry, and this covers about 90% of basic hobbyist filtering needs.

If you plan on building your own power regulators or buck converters, you will need toroidal inductors. Go with values like 10uH, 47uH, and 100uH to start with. Look for high current ratings, at least 2 or 3 amps. Power inductors are rated by how much heat they can handle before start having problems.

For noise management, you may also want to acquire a few ferrite bids. There aren’t technically coils, but they are essential. They are basically small cylinders of ferromagnetic material. You slide them over wires to choke out high frequency interference. If your project has a buzzing sound in the speakers or a flickering screen, a ferrite bead is often the cure.

Finally, if you are serious about inductors, a standard multimeter won’t cut it. Most cheap multimeters can’t measure inductance.

In such case, I recommend to pick up a cheap TC-1 Multi function tester, which you can find for about $20, and you can just plug an unknown inductor in, and it will tell you the value and the internal resistance instantly.

Better yet, buy a LCR meter, which will allow you to make precise inductance measurements, as well as capacitances and resistances. Some devices can even provide you with a full model for the component you are testing, giving you both its resistance, the series inductance, and the parallel capacitance, which is useful should you decide to work with high frequencies.

Conclusion

To summarize what we said so far:

inductors are everywhere. They are in your phone’s wireless charger, the crossover in your high end speakers, the massive transformers on your street corner, and so forth.

- They store energy in a magnetic field.

- They resist changes in current.

- They are the high frequency blockers of the electronics world.

In our future videos of this series, we are going to continue our journey in the world of electronics, showing new types of components, and how to use them, as well as moving the first steps in designing you own circuits.

If you find this deep dive helpful, like it and subscribe.

I’ll see you in the next episode and, in the mean time…

Happy experiments!

Companion YouTube video: