Welcome back to Back To Basics, our journey to master electronics one little bit at a time.

Think of your favorite gadget. Your phone, your laptop, even your car. Now, imagine if they just… stopped working. Not because the battery died, but because they couldn’t handle the noise of their own electricity.

Most people know about batteries but, today, we are talking about the unsung hero of the circuit board: the capacitor. It’s the component that can dump its entire energy load in a millisecond, smooth out a jagged power supply, and even keep your clock running when you pull the plug.

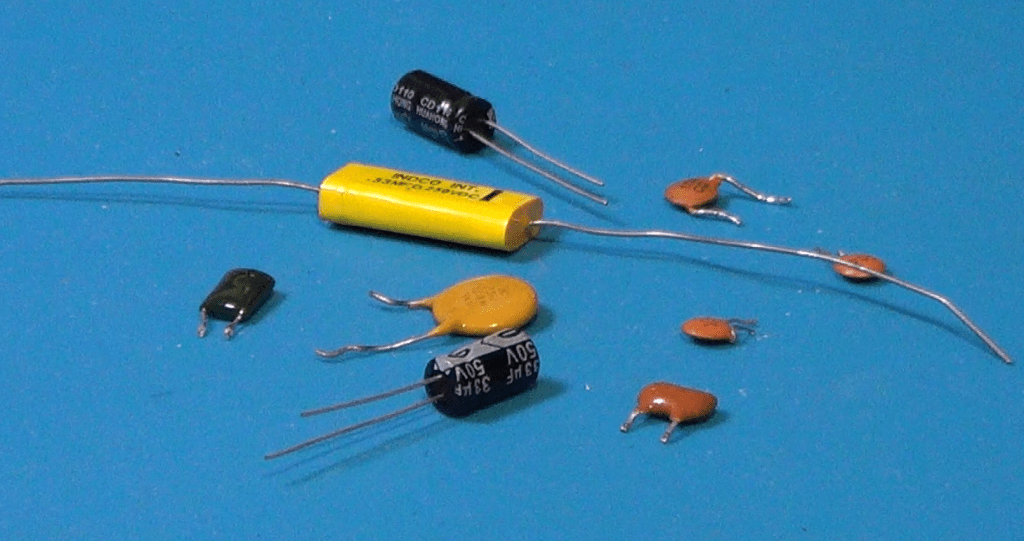

Today, in back to basics, we dive into the world of electrostatic storage. Let’s find out how these little cans and disks actually work.

What Is A Capacitor

Basically, a capacitor is a passive component that stores energy in an electric field. Unlike a battery, which uses a slow chemical reaction, a capacitor is all about speed.

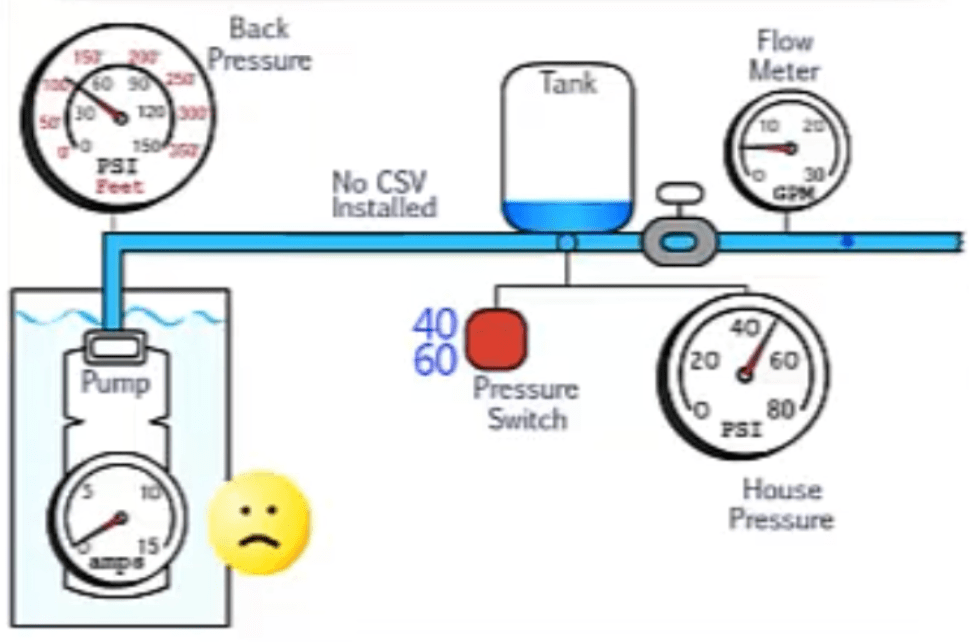

To visualize this, imagine a plumbing system. If a battery is a huge water reservoir, a capacitor is a small pressure tank. It can’t supply water for hours, but if the main pump flickers for a second, the pressure tank kicks in instantly to keep the flow steady. It’s the ultimate shock absorber for electricity.

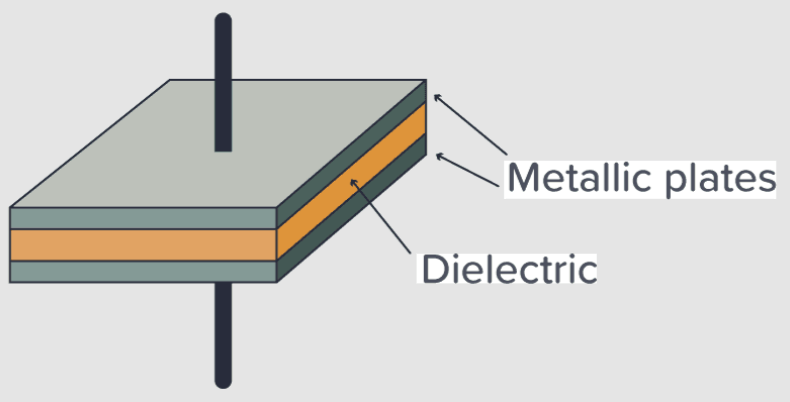

It is made of three main parts: two conductive plates, and an insulator in between, called a dielectric. When we apply voltage, positive charges pile up on one plate, and negative charges pile up on the other. The charges would like to reach each other, but the dielectric stops them. That tension is actually stored energy inside the capacitor in the form of an electric field generated by those charges.

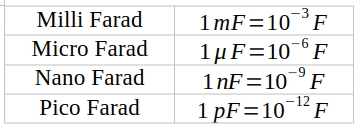

We measure the ability to store charge in Farads. But, because a single Farad is actually a huge amount of energy, we most often use a small fraction of it: the millifarad, the microfarad, the nanofarad, and the picofarad.

Top Three Applications

Why do we actually use capacitors?

There are three big roles for them:

- filtering and smoothing, where they turn bumpy DC voltages into a smooth and steady line.

- energy storage, where they can provide a quick burst, for example for a camera flash or a subwoofer’s bass hit

- signal coupling, where they allow AC signals, like music, to pass through a circuit, while blocking unwanted DC offset.

Now, not all capacitors are built the same. Here are three types that you’ll see the most often.

Ceramic capacitors: small, cheap, and non polarized, which means you can plug them either way. They look like little lentils and are perfect to deal with high speed filtering.

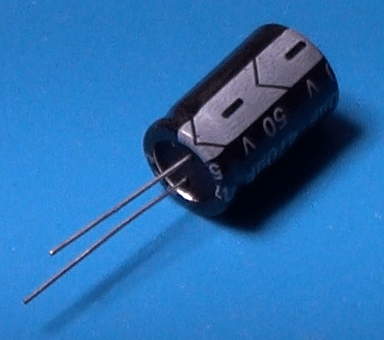

Electrolytic capacitors: these look like miniaturized soda cans. They hold a lot of energy but they are polarized, meaning they have a positive and a negative side. Hook them up backward, and things will get really messy. They are perfect for low speed filtering, for example in DC power supplies.

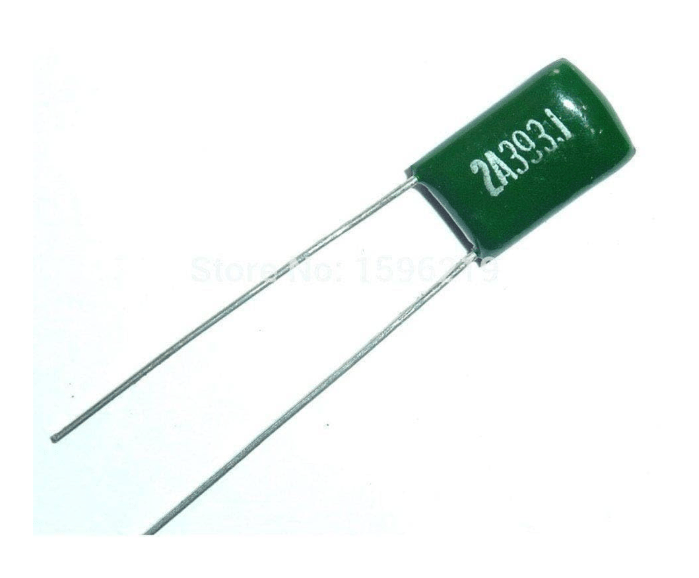

Film capacitors: Usually rectangular and green or red. These are very stable and great for audio circuits or high voltage power.

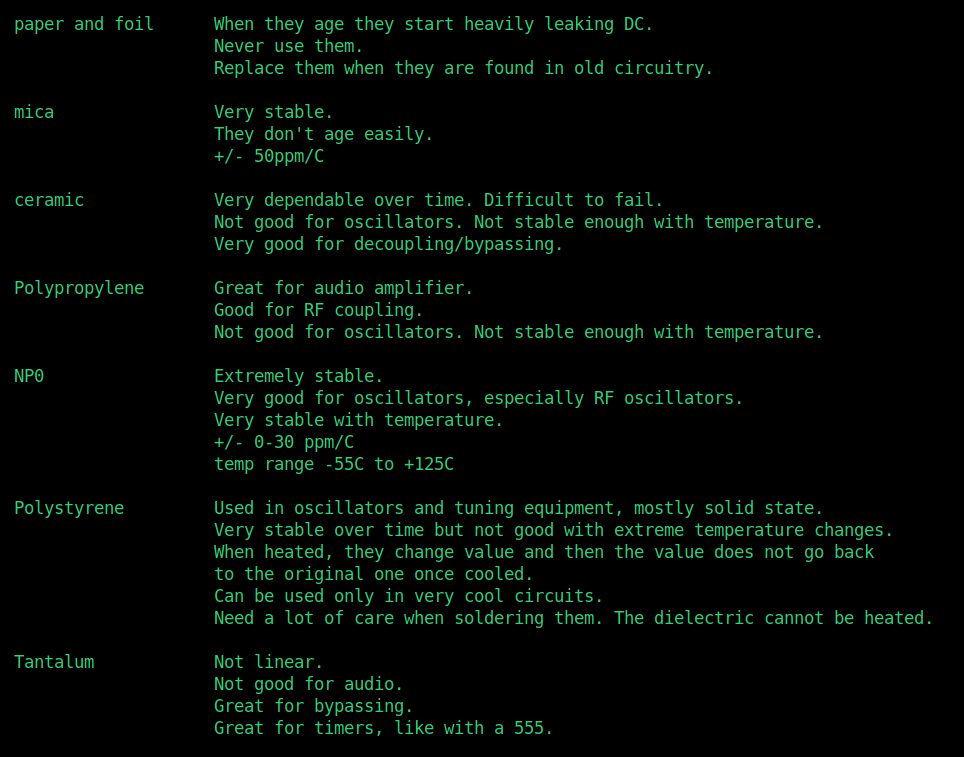

And, just to give you the full picture, here is a table I made where all the type of capacitors are listed.

In here, note that NP0 capacitors are a special kind of ceramic capacitors. Polystyrene and polypropylene are the typical dielectrics of film capacitors. Tantalum capacitors are a type of electrolytic capacitors, where the positive plate uses tantalum metal, and the dielectric is made oxidizing one side of the tantalum plate. As the other kind of electrolytic capacitors, these are also polarized.

Identify The Codes

OK, let’s say now we got a bunch of capacitors, all there sitting on the workbench. But how do we know which one is which? Unlike resistors, which use color bands, capacitors use numbers and letters printed on their body. The big problem is, different types of capacitors don’t speak the same language. And… yes, sometimes even same type capacitors don’t.

Let me tell you the most common ways to interpret the information on the capacitors cases.

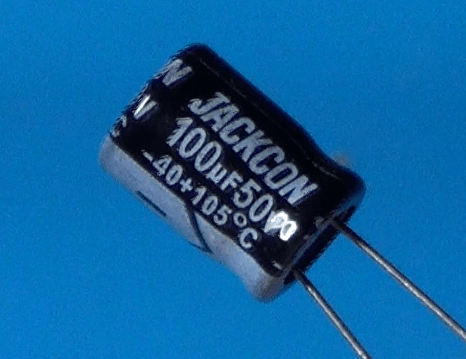

And let’s start with electrolytic capacitors. They are the most straightforward, because they are physically larger, and the manufacturers have enough room to print the actual values directly on the side.

The capacitance is a number followed by the Greek letter mu and a capitol F, which stand for microfarads. For example, this one says 100uF. No math required.

Follows the maximum voltage rating, in this case 50V. Remember that you have to always use the capacitor at a voltage smaller than the rated voltage, or you’ll damage the capacitor.

Last, we have the polarity, this big stripe with the minus sign. That stripe indicates the negative lead of the capacitor. Note also that in an electrolytic capacitor, the negative lead is also shorter than the positive one.

Let’s now take a look at the ceramic capacitors. These capacitors are too small for full labels. Instead, they use a three digit code and their unit is always expressed in picofarads, or pF. The first two numbers are the value, and the third number indicates how many zeros you have to add to the previous two digits to provide their value in picofarad.

Additionally, when the number of picofarads is very small, in the order of only one or two digits, then the value can be directly expressed with those digits. In that case, we have only one or two digit numbers.

For example, on this one we read the digits 1-0-4. That means we have a 10 followed by 4 zeros. That gives us the number 100,000, so the value is 100,000 pF, or 100nF, or 0.1uF. And yes, we need a little math to interpret the values of these capacitors.

Here is another ceramic capacitor. This one has only two digits printed on it: 3-3. This means that the number 33 is the nominal value of the capacitor in pF.

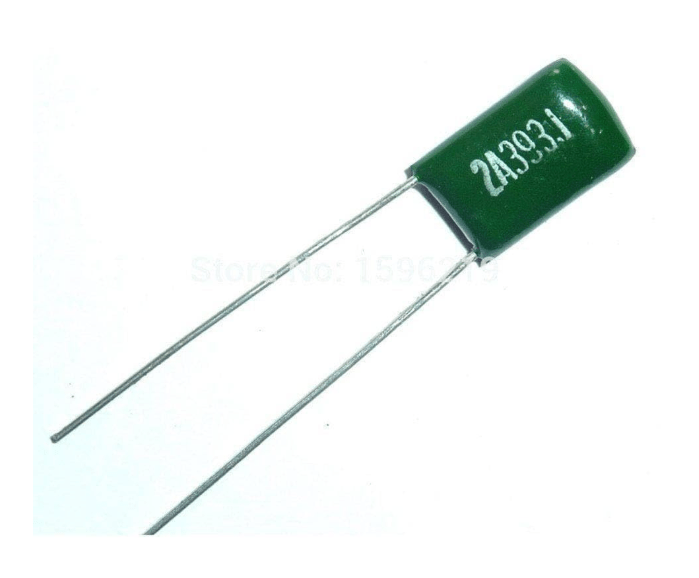

Lastly, let’s take a look at a film capacitor.

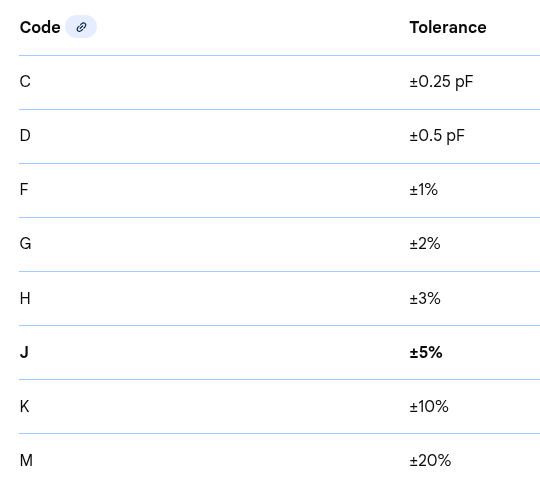

These capacitors often use a mix. You might see a 3-digit code, like the ceramics, but you will also see a letter at the end. That letter represents the tolerance, or how accurate the nominal value actually is.

But wait, there is more: the rated voltage. This one can be expressed in three different ways. It can be written explicitly, or it could be missing, of there could be a code which is prefixed to the capacitor value.

If it is expressed in clear, then that is the actual rating.

If the voltage rating is not present at all, then it is 50V by default.

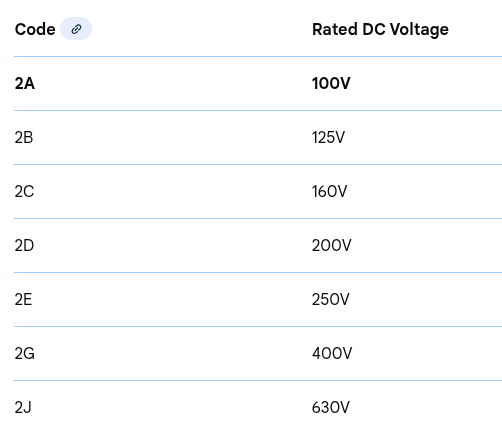

If it is encoded along with the capacitance value, then it can be one of those listed in the EIA standard. Here is the corresponding table for the most common.

As an example, the film capacitor above reads: 2A393J.

2A translates into a voltage rating of 100V; 393 translates into a value of 39,000pF, or 39nF, and the letter J at the end translates into a tolerance of 5%.

Here is the hole list of tolerances.

A pro tip for you now, valid for any kind of capacitor. If the text is rubbed off, or too small to read, or has any other problem that prevents you from reading it, don’t guess. Use a multimeter capable of reading capacitance. It will give you the live reading of exactly what that component is holding, and it’s the only way to be 100% sure before you solder the component in a circuit.

Pitfalls

Okay, now that we have covered some theory and some practical aspects, it’s time to take a look at what I call the ‘Wall of Shame’. If you stay in this hobby long enough, you will eventually blow up a capacitor. It’s almost a rite of passage! But to save you the jump-scare and the smell of burnt electrolyte, I want to show you the most common ways people accidentally kill or misuse their capacitors—and how you can avoid doing the same.

Here is my list #1 mistakes every beginner makes and how to fix or prevent them.

- The polarity POP or: connecting an electrolytic capacitor backward. The consequence is that the internal dielectric breaks down, the electrolyte boils into gas, and pressure builds up until the safety vent bursts, or the whole capacitor pops. To prevent that, always look for the stripe on the side of the capacitor, which marks the negative lead, or look for the longer leg, which marks the positive lead.

- Ignoring the voltage rating, or using a capacitor that is rated exactly for the voltage of the circuit or. worst, a capacitor with a smaller rating. In such a case, an excessive voltage can push the capacitor over its limits, causing it to leak or fail prematurely. Avoid that by always leave a safety margin. Use a capacitor rater 20 to 50% higher than the circuit voltage. If the circuit works at 12V, use a 16V or even a 25V capacitor.

- The ghost charge. This has more to do with safety. Don’t assume a capacitor is off just because the device is unplugged. Capacitors, especially if large, can hold a dangerous charge for days or even weeks. Touching the leads can give you a nasty shock, or damage the multimeter if connecting the charged capacitor to it. Before handling the capacitor, discharge it. This can be safely done using a high value resistor ,like 1k, to bleed the energy off slowly.

- Wrong type for the job, for example when using an electrolytic capacitor when a ceramic one should have been used instead. The result is usually an erratic behavior of the circuit. For example, using a large electrolytic capacitor near a micro-controller can cause the random reset of the micro-controller itself, because of the random electrical noise on the power line that the capacitor cannot get rid of. In such a case a small ceramic capacitor should be used for decoupling. Remember: electrolytic capacitors are good for bulk energy storage, ceramic capacitors are good for high speed noise filtering.

- Soldering stress, or thermal shock. Holding the soldering iron on the capacitor leads for too long causes excessive heat that can dry out the electrolyte inside an electrolytic capacitor, of crack the ceramic layer of a ceramic capacitor, or melt the dielectric of a film capacitor. Always use a clean and tinned iron tip to be able to do make good soldered joints is a short time. You may want to see my video on soldering techniques for further information.

The Essential Capacitor Starter Kit

Before closing, here are some suggestions to create your own capacitors starter kit, an assortment of capacitors that covers 95% of the necessities for beginners projects, like Arduino, LED circuits, simple audio circuits, and so on. Start with a mix of ceramic and electrolytic capacitors. You can add more later.

Ceramic capacitors will be useful as non polarized noise killers. They are used for decoupling and filtering high frequency noise.

Useful values are:

- 22pF, essential if you are building your own micro controllers, ad they are used in crystal oscillators.

- 0.1 uF, the most common capacitor in existence. Every integrated circuit usually needs one of these right next to its power pin.

- 1uF, good for general purpose filtering

Electrolytic capacitors will be useful as polarized power smoothers. These are bulk energy storage for power supplies. The most common values for beginner projects are:

- 10uF, 25V or 50V. used for small scale power smoothing.

- 100 uF, 25V. Great for stabilizing power rails in breadboard projects.

- 1000uF, 25V. The big tanks. Used when dealing with motors or long LED strips of LEDs that pull a lot of current.

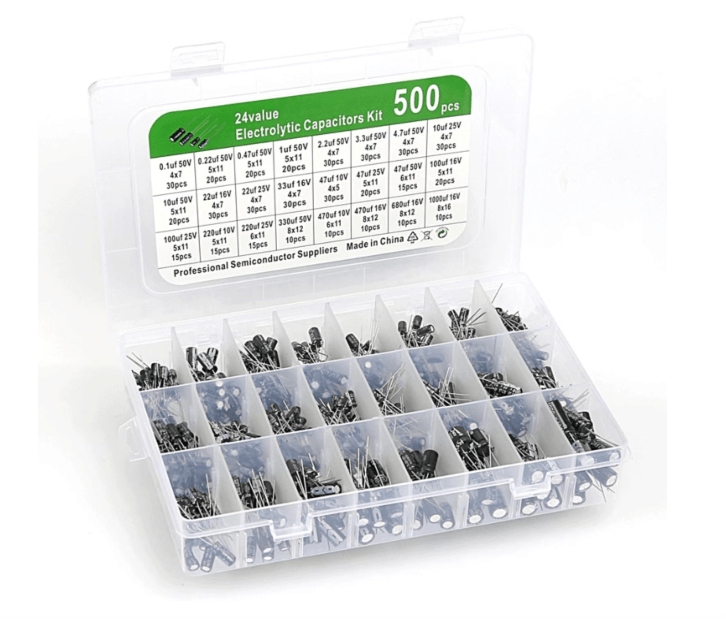

As an alternative, rather than buying individual values, search for capacitor assortment kits, on sites like Amazon, Adafruit, or Ali Express. They usually come in a plastic organizer box and are very cheap.

When buying a kit, look for capacitors rated at 25V or 50V. While 16V capacitors are smaller, a 50V capacitor can do everything a 16V one can, making it much more versatile for a beginner who might accidentally plug it into a 24V source.

Conclusion

So, there you have it: the humble capacitor. It is not just a tiny battery; it is the heartbeat and the filter of almost every circuit you’ll ever build.

I’ll see you in the next episode, and in the mean time…

Happy experiments!!!

A capacitor is an electric device capable of storing energy in the form of electric charges (electric field).

A capacitor is an electric device capable of storing energy in the form of electric charges (electric field).